Zoning Controls Your Life, But It Has Dark Origins

A court case calls apartments parasites and compares renters to pigs. It’s the foundation of residential zoning rules that govern everyone’s homes.

Residential zoning controls more about our lives than most people realize: where you grow up, who your friends and classmates are, how far away the nearest store is and what transportation you use to get there. In nearly every American city, zoning maps determine which types of housing, and therefore which types of people, are allowed in different neighborhoods.

Most of the built environment in our towns and cities conforms to rigid rules ranging from the straightforward to the arbitrarily complex. Early zoning codes governed simple characteristics like the height and density of buildings. Over time, they have evolved to dictate minute details like the distance a building must be set back from the property line, the ratio of building floor area to lot size, the “daylight plane” from the building roof to the street, the diagonal line from one corner of a building to the other, and dozens of other standards that put a normal person to sleep.

What if all residential zoning rules were based not in science nor in necessity but in prejudice? A little-known supreme court case reveals the controversial origins of modern residential zoning. Even housing experts familiar with the decision often don’t know its lurid details.

Origins of Residential Zoning

Start with the codes themselves: Industrial zoning was invented in the 1900s to separate where people live from noxious factories. Los Angeles implemented the first large-scale residential-only zoning in 1904, banning laundries and wash houses from some residential neighborhoods. Sure, the LA ordinance partly intended to separate Asian families from living near white ones. Its authors were racist. But the concept of keeping factories away from residences makes some sense.

Zoning evolved in an era of utopian rationalism. A group of idealists thought the rules could be expanded to govern all residential development, bringing order to the chaos of industrializing cities at the time.

New York City enacted the first citywide zoning ordinance in 1916 because some residents felt the Equitable Building, an ornate skyscraper, was too tall and shadowy.

NYC’s original code exclusively governed building heights, but it was just the beginning. The Equitable Building ushered in a new era of inequitable zoning rules.

That same year, the City of Berkeley implemented the first single-family only zoning, mandating no more than one home per lot. A Berkeley real estate developer invented single-family zoning to prevent a Black Dance Hall from moving into his racially segregated neighborhoods.

Similar zoning rules spread nationally in large part because President Herbert Hoover loved rules and standardization. Hoover convened a group of people, led by the primary author of New York’s zoning rules, to write a standard platform for zoning across the entire country. State and municipal governments voluntarily adopted the platform almost universally.

Prejudice Embedded in Law

Fast forward to 1926, and the Supreme Court affirmed the legality of residential zoning in the Euclid v. Ambler case. The particulars of the case matter less than the logic used to justify its conclusion, that cities can legally use residential zoning to segregate some types of housing from other types of housing.

In Euclid, the Supreme Court claimed that apartments harm the “public health, safety, morals, or general welfare” of residential neighborhoods. The Court compared apartments—and the renters who live in them—to “a pig in the parlor instead of the barnyard.”

The Court wrote “very often the apartment house is a mere parasite … the coming of one apartment house is followed by others, interfering by their height and bulk with the free circulation of air and monopolizing the rays of the sun which otherwise would fall upon the smaller homes, and bringing, as their necessary accompaniments, the disturbing noises incident to increased traffic and business … thus detracting from their safety and depriving children of the privilege of quiet and open spaces for play … until, finally, the residential character of the neighborhood and its desirability as a place of detached residences are utterly destroyed.”

Anyone who has been to a recent city council meeting discussing development has heard all of these complaints about new housing. Traffic! Safety!! Shadows!!! What about the children?!!?!?

People should have the freedom to live in a house of their choosing that they can afford, including a single-family home. But should they have a right to use the power of government to block anything except a single-family home near them?

The supreme court, writing from an earlier time, clearly states the subtext of the government’s residential zoning power: Apartments are like parasites, renters like pigs. All residential zoning rules derive from the prejudiced foundation of Euclid v. Ambler.

The Long Shadow of Euclid

Hidden by a veil of legalese and boringness, residential zoning codes have spread across the nation, becoming stricter than their progenitors could have ever imagined.

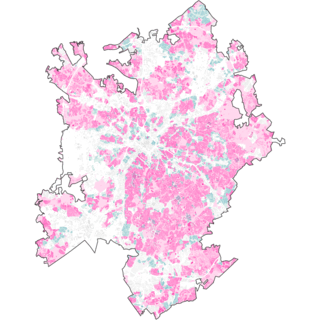

UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute mapped zoning codes across the Bay Area and found 85% of all residential land bans apartments—and the renters who live in them.

Caption: All of the pink area bans apartments and the renters who live in them.

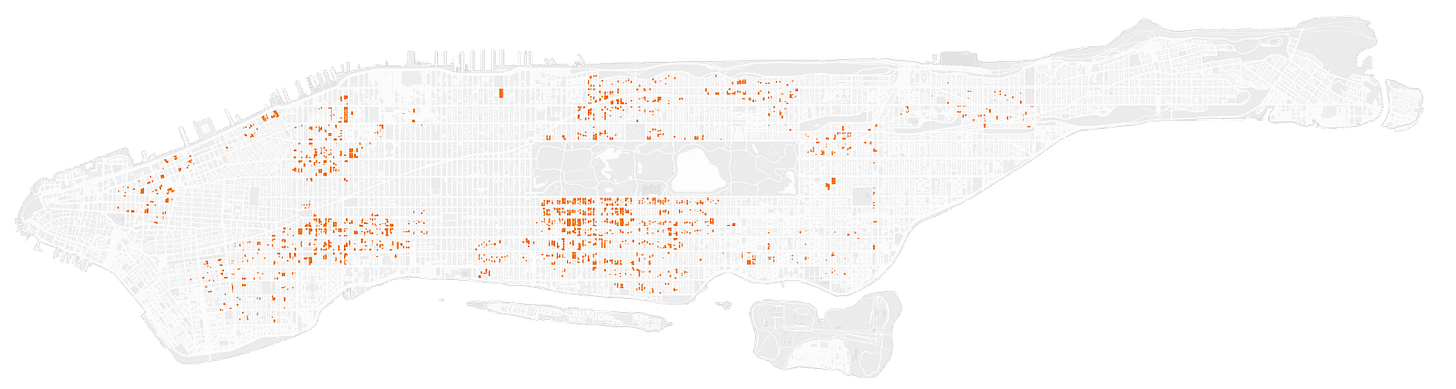

A New York Times investigation found 40% of buildings in Manhattan, the densest area in America, would not be legal to build under current zoning rules.

Because They Are Too Tall ...

Or They Have Too Many Apartments ...

Or Too Many Businesses.

Every part of the country has similar rules banning apartments in some neighborhoods and restricting them everywhere else.

Charlotte, North Carolina has 84% single-family only apartment bans.

Arlington, Texas, has 89% single-family only apartment bans.

Look at any random small- to medium-sized town in America and their zoning is often even more restrictive. In my hometown of Lafayette, California, a whopping 98% of residential land bans apartments.

The vast majority of residential zoning rules, especially single-family only apartment bans, make housing artificially expensive, entrench segregated living patterns, and kill economic growth. Rates of racial segregation and the racial homeownership gap today remain just as high or higher than they were in 1960—when explicit segregation was legal!—in large part because of zoning rules. And the codes are based on a century-old court case with no scientific basis.

Building for the Future

The growing “Yes In My BackYard” YIMBY movement presents an alternative to the core assertion of Euclid v. Ambler: Housing is compatible with other housing, no matter the type. Apartments are not parasites. Homes do not pose a threat to the “public health, safety, morals, or general welfare,” even if some of the homes are taller than others. More neighbors make our neighborhoods more vibrant. We need rules that allow abundant housing for everyone.

Some forms of zoning still make sense, especially industrial zoning. Environmental factors may make some neighborhoods unsafe for new development, in which case we should be proactively retreating from them rather than just limiting growth.

Fundamentally, though, residential zoning truly focused on the general welfare would be much more limited in scope than current standard models. To crib from Atlantic editor Yoni Applebaum: All neighborhoods should allow consistent growth, codes should be universally tolerant of different built forms, and the ultimate goal of zoning should be safe, abundant housing for all.

Rewiring residential zoning to focus on the general welfare will likely require new Supreme Court precedent or a constitutional amendment. Both seem unlikely anytime soon under a presidential administration that seems to think deportations, not legalizing housing, will solve our zoning-induced shortage.

In the meantime, local political activism can make a huge difference. Cities have the power to unilaterally change their own zoning themselves. To do so, our leaders need to hear from constituents like you, dear reader, that you want the status quo to change. That you want to see new homes of all kinds and new neighbors. Join your local neighborhood housing organization—or start a new one! Write a letter to your local elected official asking for more housing. Be the change you want to see in local government.

At a time when national politics feels hopelessly fraught, we can influence the destinies of our communities and our country to be more free, affordable, inclusive places. It all starts by changing the codes governing our own neighborhoods.

This article draws on information from several books, including Zoning Rules! by William Fischel, How to Hide an Empire by Daniel Immerwahr, and The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein.

Very well done, Jeremy.

You tell a sad story well.