Making Strong Towns a Stronger Movement

How to create an absolutely JACKED urbanist organization

As much as I write about building unity in the housing movement, I love a little drama. So I have greatly enjoyed the recent Substack debate between various “yes in my backyard” YIMBY writers and the Strong Towns organization, two mostly aligned factions of the housing movement that love to poke at each other.1

Context for those who don’t neurotically read housing Substacks

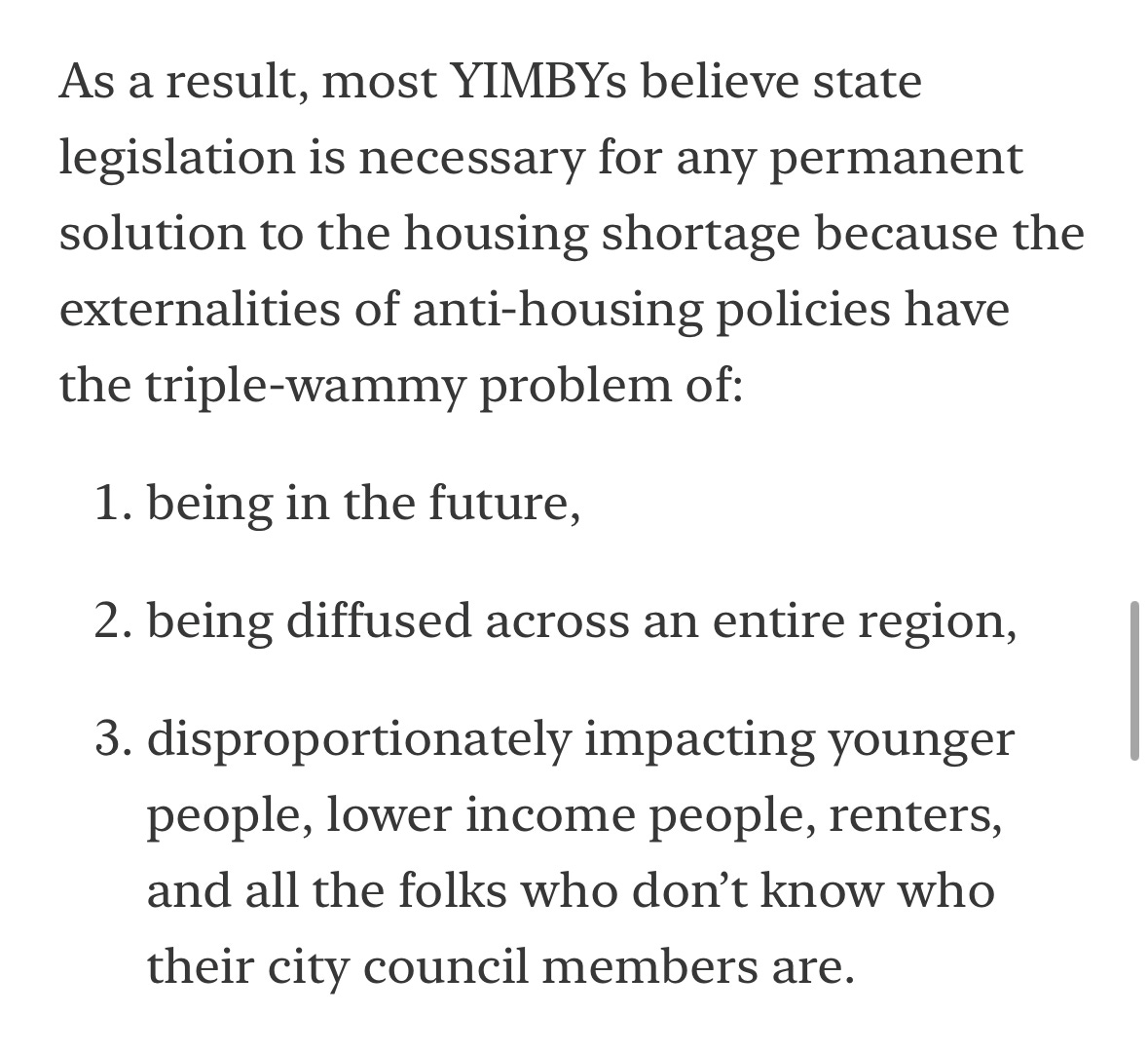

Before I add my two cents, an overview of past discourse: The debate has largely occurred about local control versus state preemption over land use. Should cities set their own zoning rules and other housing regulations, or should state legislatures override them to allow more housing by default?

YIMBYs favor state preemption; Strong Towns generally—though not always!—prefers local control by cities.

Most recently, YIMBY Action executive director

and board member wrote an open letter to Strong Towns founder Charles Marohn arguing that Strong Towns Need Strong States. In their piece, they argue that housing shortages are regional problems, problems that most cities have little incentive to solve on their own. As a result, state legislatures must step in with solutions.Strong Towns Executive Director

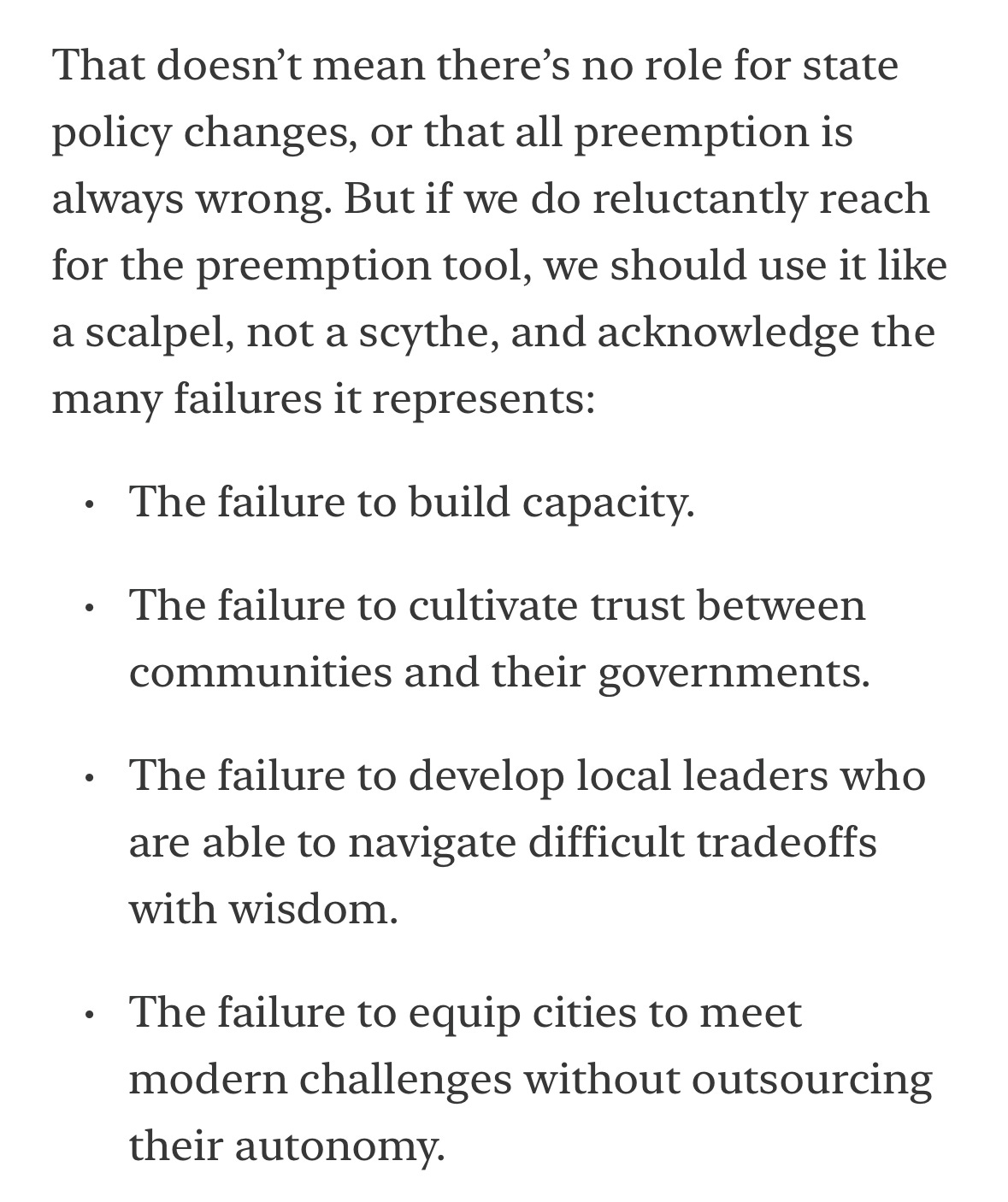

responded that state preemption has a role to play in housing solutions, but that local governments are “still our best hope for real reform.”2Charles’s sentiment reflects Strong Towns’s long-term mission “to replace America’s post-war pattern of development, the Suburban Experiment, with a “bottom-up” community planning model. “Bottom up,” by Charles’s definition, involves the residents of local communities controlling decision making, rather than professional planners or centralized institutions. Strong Towns is skeptical of centralized power, even when that power tries to allow more housing than permitted under local rules.

Finally, the point I’m here to make

I enjoy the debate over local versus state land use control, but today I want to focus on movement building: For all its emphasis on bottom-up planning, the Strong Towns movement itself is centralized, heavily reliant on one organization led by one thinker. That mismatch makes it fragile.

Movements thrive when ideas spread through many voices, growing organically. To build a stronger Strong Towns movement, the organization should embrace the type of bottom-up development it supports in local governments.

To understand Strong Towns’s top-down centralization problem, it’s helpful to compare the recent Strong Towns conference to the upcoming YIMBYTown conference.

Half the speakers at the Strong Towns conference lineup were either staff or contributing writers to the central Strong Towns org. All the keynotes were org staffers. For all its talk of ideological diversity and bottom up planning, Strong Towns thought leadership occurs top down.

YIMBYTown conference speakers look different. Keynotes juxtapose the Republican governor of South Dakota with a DEI consultant, the chief economist at Redfin with a climate activist. None of the keynotes are directly affiliated with a YIMBY orgs. Panelists come from organizations across the country (though not many volunteers—a disappointing difference between this YIMBYTown and earlier ones).

The difference isn’t just optics. It shows which movement is cultivating a broad intellectual ecosystem versus consolidating around a single group. Depending so much on the intellectual output of Charles Marohn and the organization he leads risks making the movement unable to adapt if leadership falters or its messaging struggles to resonate with new audiences.

To its credit, the Strong Towns organizing model relies primarily on bottom-up local groups, inspired by the core Strong Towns messaging. The central organization devotes resources to supporting the local groups with advocacy infrastructure, communications tools, and educational resources that can support local arguments.

However, Strong Towns lacks the diffuse organizing structure of the much more distributed YIMBY movement. Outside of the name-brand Strong Towns org, there are no professionalized organizations that advance Strong Towns’s particular messaging.

In contrast, multiple professional YIMBY organizations provide support for local volunteer-led YIMBY chapters. A single state-level organization, California YIMBY, has the same number of staff as Strong Towns, and it’s just one of dozens of such orgs. The YIMBY movement’s early founders remain influential, but they don’t hold nearly the same brand control as Strong Towns.

Furthermore, Strong Towns has few connections with academic researchers or think tanks, organizations that do much of the intellectual development free of charge for the YIMBY movement. Instead, Strong Towns produces most of its intellectual input in house. That output is impressive, but sometimes feels insular without the legitimacy of academic peer review.

Some of the differences between YIMBY and Strong Towns maybe reflect differences in movement priorities. Strong Towns may be averse to professionalizing because of its commitment to local, volunteer-led leadership. Giving up tight brand control contains perils, including the potential for conflicting opinions to arise.3 Strong Towns seeks to build something different from YIMBYism, and the movement may need to look different as well.

Building a resilient housing movement

Still, Strong Towns’s current centralized organizational structure, with most thought leadership produced by a single organization, centered on a single man, reflects the very sort of fragility that Strong Towns seeks to address in local governments across the Country.

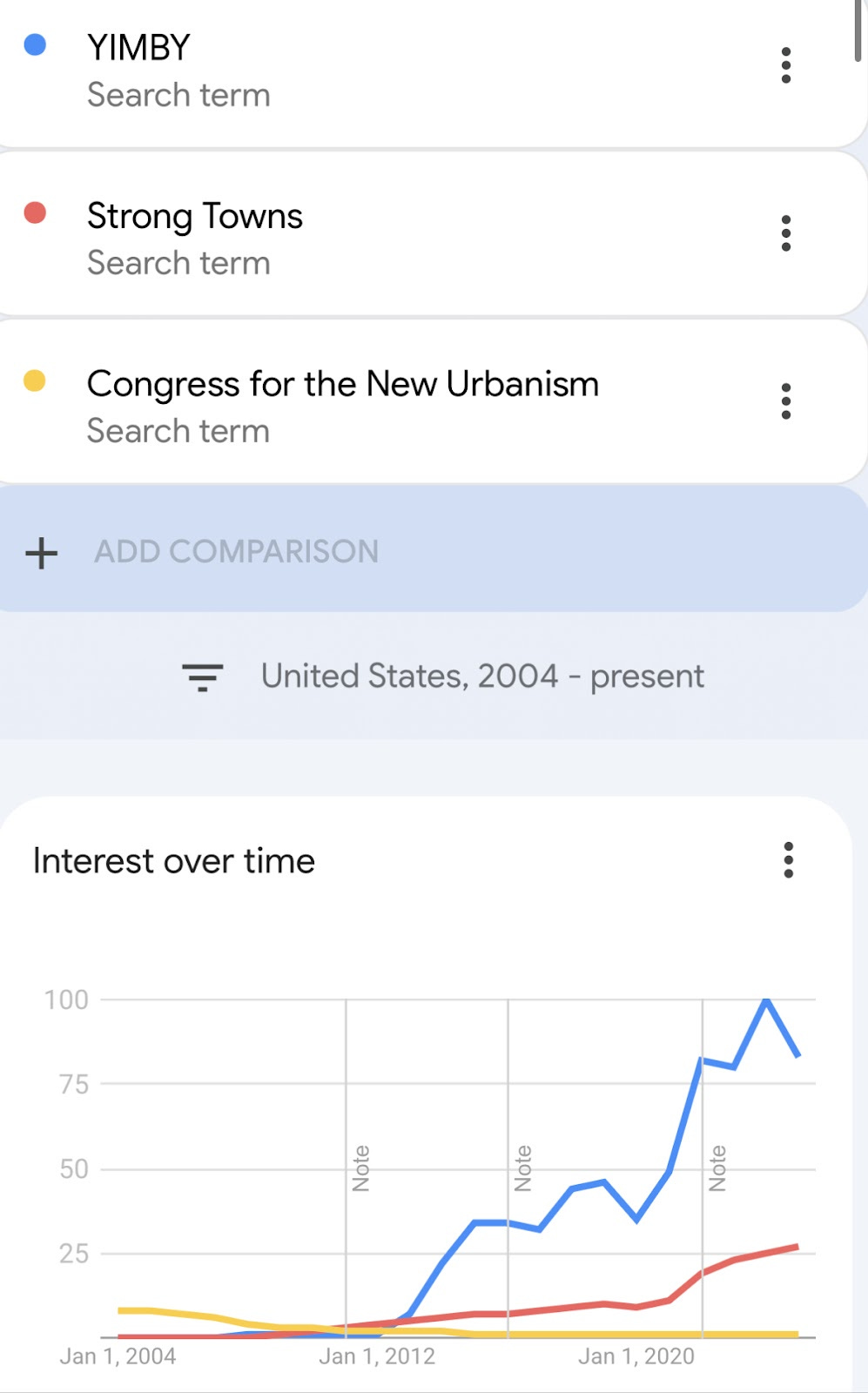

If Strong Towns remains so centralized, it could end up like the Congress of New Urbanists, once influential, now largely irrelevant. (Though that’s not a real pressing issue yet; Strong Towns has slowly but steadily gained interest with time since its founding more than 15 years ago, according to Google search trends.)

That would be a pity. Strong Towns emphasizes key insights that benefit the housing movement writ large, particularly related to municipal finance, traffic engineering, and incremental neighborhood evolution. It has a particularly strong Midwestern appeal that expands the movement’s geographic reach.

To broaden its appeal yet further, Strong Towns can grow stronger by better practicing what it preaches, inviting in outside thinkers, diversifying leadership, and investing in independent regional groups with autonomy to expand and adapt its message.

Broadening its base could start by courting academics and media intellectuals. Collaborating with academia requires actively engaging outside thinkers in the fundamental questions Strong Towns seeks to answer rather than attempting to do everything in-house. Some areas for valuable research include:

The history of housing finance (covered in Charles’s own books but not many other places)

Comparing housing finance models across regions within and outside the U.S. to try and establish better causality

Financing incremental development

Zoning reforms that work in theory and are politically viable in practice

Rethinking current models of municipal finance

Next, Strong Towns could better embrace a diversity of opinion on its core issues. Most salient, Charles’s personal skepticism of state-level policy interventions flattens debate about the best political strategy for creating the sort of bottom up community planning Strong Towns supports. Strong Towns’s own board president, Andrew Burleson, has written that We Don’t Need Zoning, yet the organization continues to treat state preemption like an option of last resort rather than part of a messy toolkit to liberalize land use rules.

Other questions arise, such as how fast can “incremental” development occur? How radical of zoning reform does Strong Towns support at the state and local levels? Again, there are differences in between some Strong Towns leadership writing these issues, but it’s not clear how much diversity of thought the movement allows when it has such a small group of spokespeople.4

Lastly, Strong Towns could encourage independent professionalized organizations to take up the Strong Towns mantle with their own local or regional flavor. Strong Towns’s “local conversations,” its version of chapters, do on-the-ground local organizing. But they all exist under the centralized Strong Towns brand. The organization would benefit from new fundraising strategies that involve directing more money to priority areas, building more tangible political power to facilitate the sort of cultural shifts to which it aspires.

Diversifying the movement’s spokespeople may require identifying and embracing more concrete, scalable advocacy goals—potentially including more proactive, unflinching support of policy change at the state level along with local advocacy.

Whatever path the organization takes, it will be most resilient by making space for bottom up and spontaneous growth, just like the urban planning practices Strong Towns seeks to normalize.

Learn more about the differences between YIMBY and Strong Towns with this spiffy guide I wrote here.

For other fun entries in the local control versus preemption debate, check out

Journalist

’s epic debate with Charles over AbundanceSubstacker

on Subsidiarity and PreemptionStrong Towns board president

on ZoningSubstack

on whether zoning authority is ever legitimate

Charles once wrote “one of [the YIMBY movement’s] defining characteristics as a collection of people is internal division”—a tad harsh but not entirely inaccurate.

In the comments of his post on preemption, I asked Charles “When do you see state preemption as ‘lending assistance to cities that are struggling’ versus ‘systematically weakening our cities for short-term expediency’?” (Quoting text from his article.) He responded “If we think of preemption as a scalpel to help stuck cities get past some bad legacy practices, then I think we're working for the same thing. If we approach this as a bludgeon to strip cities of power and put them in their place, then I think we have the wrong framing.” That’s not a very clear answer, but I think that’s fine—a strong movement allows space for different advocates to decide what they think the scalpel versus the bludgeon looks like.

@jeremy levine - I am part of the Strong Towns org and a lot of what you wrote is reflected in ongoing conversations around our strategy, focus, and efforts to continue to cultivate a movement. I left a note below about the conference lineup because you missed some key details but it's certainly the case that:

"To broaden its appeal yet further, Strong Towns can grow stronger by better practicing what it preaches, inviting in outside thinkers, diversifying leadership, and investing in independent regional groups with autonomy to expand and adapt its message.

Broadening its base could start by courting academics and media intellectuals. Collaborating with academia requires actively engaging outside thinkers in the fundamental questions Strong Towns seeks to answer rather than attempting to do everything in-house."

It may not be as visible externally but there is a tremendous amount of knowledge transfer occurring with our Local Conversation groups. They are very independent (we ask them to sign a "don't be a jerk" agreement, to not endorse candidates, and to distinguish their logo and name from the main org).

If you have suggestions on how to court academics and media intellectuals more, we're all ears! As @seth zeren has explained, a major shift needs to occur in education and it feels like we need to do some of this ourselves (with strong partners) because there's so much inertia in academia.

"Half the speakers at the Strong Towns conference lineup were either staff or contributing writers to the central Strong Towns org. All the keynotes were org staffers."

?

That's not correct - Chris Arnade was the keynote speaker. Same with Barkha Patel last year and Majora Carter the year before.

The majority of the session leaders were non-ST, Joe Minicozzi, Vanessa Elias, Vignesh Swaminathan, etc.

Very curious how you came to that conclusion.